Home > Themes > What is the Caribbean ? > The perceived Caribbean: An Introduction

The perceived Caribbean: An Introduction

CubaEN

CubaEN

The demarcation of the boundaries of the Caribbean varies considerably based on the aspects considered: language(s), identity, oceanography, economy, history, culture, geopolitics, etc. (Girvan 2005). The exonym “Caribbean”, a legacy of the European vision of the World, was only established to designate the region at the end of the 19th century, during the expansion of the United States into the Basin (Gatzambide-Geigel 1996). Caribbean is thus an unfortunate toponymic label, derived from the European perception of the Kalinago Indians as man-eaters (whom they called “Caribs”, the root from which the words Caribales, and later Cannibals, were formed), and popularised during the geopolitical expansion of the United States. Moreover, it is used to describe spaces of different dimensions (physical, cultural, political, etc.), which are often not perfectly juxtaposed.

In addition to the toponymic problem, the geographer articulates the need to take an interest in the space as it is experienced by its populations (Frémont 1976). At this level, it is no longer a question of defining the Caribbean region using various indicators, but of understanding how the regional actors themselves perceive the boundaries of their territory – i.e. the space that they identify with psychologically. Indeed, man does not evolve in the space as it is, but rather in the space as he perceives it (Thomas-Hope 2002). The way in which a regional space is perceived by those who live in it and bring it to life cannot be ignored when seeking to demarcate its borders.

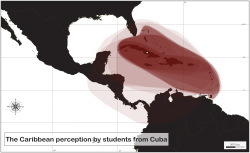

This article offers a brief introduction to the Caribbean, as it is experienced and perceived, by presenting the cartographic vision of undergraduate students in various regional universities. The maps presented here show a superimposition of the drawings of the Caribbean produced by the students. The samples generally consist of approximately 50 students. To the many teachers who contributed by collecting the information, we extend sincere thanks for their participation.

The first remark inspired by these maps is as follows: The Caribbean, as it is perceived and experienced from within by these students, is primarily the archipelagic arc, the “peninsula” (Cruse 2009) that links Venezuela to the United States by a dotted line. However, the boundaries of this zone are quite blurred. At the extreme south, for example, Trinidad is often omitted as if the island were part of the South American mainland, with which it shares a geological history. Conversely, the two independent Guianas (Suriname and Guyana), as well as Belize, are quite frequently included in the perceived Caribbean space. This is particularly true with respect to the English-speaking students, who frequent students from those territories on their campuses. The definitions of the “insular Caribbean” (Girvan 2004), the sugar cane sub-category of “plantation America” (Best 1971) and “Central Afro-America” (Gatzambide-Geigel 1996), which include both the islands and the insularised portions of the continents, correspond relatively well to the Caribbean as it is perceived by these students.

In rare cases, the boundary of the perceived Caribbean is extended to the coasts of Central America, Colombia and Venezuela (the “continental” Caribbean). It is noteworthy that although these regions are rarely included by external students, students from Cartagena, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, see themselves as belonging to the Caribbean space. It is evident that the “Greater Caribbean” (insular Caribbean, Venezuela, Colombia and Central America) is not yet entirely a construction that is experienced as such.

The Guianas (Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana) are generally less represented than the islands, but rarely ignored. They appear as blurred margins of the Caribbean space. However, this is less the case as one draws closer to these territories. Thus, Trinidadian students include Guyana and Suriname much more frequently. In general, the English-speaking Guyana is more often linked to the Caribbean than the Dutch-speaking Suriname. The French-speaking French Guiana, which is more outlying and quite difficult to access, is virtually never included in the Caribbean space as it is perceived by these students. The Spanish-speaking Cuban students simply do not include these physically, linguistically and culturally remote spaces in “their” Caribbean. These examples underscore the importance of the linguistic and cultural determinants as well as the distance/accessibility pair.

The situation varies with regard to the outlying islands of the insular arc that are bathed by the Caribbean Sea. The islands located along the coast of Central America (the Bay Islands, Cozumel, etc.) are generally excluded from this perceived Caribbean. However, the Dutch “ABC” islands (Aruba, Curacao, and Bonaire), which are situated off the coast of Venezuela in close proximity to Lake Maracaibo, are included, albeit relatively marginally. Conversely, the insular territories that are not bathed by the Caribbean Sea, but located in direct proximity to the Antillean Arc, and connected by significant migratory flows to the rest of the Caribbean (The Bahamas, Barbados or Turks and Caicos, for example), are almost always included in the perceived Caribbean.

The vision of the students from the French-Caribbean Overseas Departments reveals the identity problem that is characteristic of these spaces. On the one hand, the majority of the students born and educated in Martinique, Guadeloupe or French Guiana, do not consider themselves “Caribbean” (Cruse 2011). However, based on their cartographic representations, their respective territories belong to the Caribbean space (except in the particular case of French Guiana). These students seem to be aware of the fact that they are enveloped by the Caribbean, but turn their back on it. Cognisant of their significant cultural differences with the French from “France” (or the “Metropolis”), they are also equally at odds with the rest of the Caribbean. They are strangers in both their national and regional environments. They have thus re-created a special identity that they call “Antillaise”, which pertains to both Martinique and Guadeloupe. In the case of French Guiana, they have quite a distinct perception, encompassing France, the Caribbean and Amazonia. (For further details on this point see Cruse and Samot 2011).

Catégorie : What is the Caribbean ?

Pour citer l'article : (2013). "The perceived Caribbean: An Introduction" in Cruse & Rhiney (Eds.), Caribbean Atlas, http://www.caribbean-atlas.com/en/themes/what-is-the-caribbean/the-perceived-caribbean-an-introduction.html.

Références

Best L. (1971). « Independant thought and Caribbean freedom », New World Quarterly, Vol 3., n°4.

Cruse R. (2009). L'Antimonde Caribéen, entre les Amériques et le Monde. Thèse de doctorat, Université d'Artois, 2 vol., 735p.

Cruse R. (2011). Identités Antillaises, Enquête statistique conduite à l'Université des Antilles et de la Guyane, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guyane, Non publiée.

Cruse R. et Samot L. (2011). « Les Antillais sont-ils caribéens ? » in Cruse R. (Ed.). Caribbean Atlas, Université des Antilles et de la Guyane, University of the West Indies, www.caribbeanatlas.com.

Frémont A. (1976). La région, espace vécu. Paris Flammarion.

Gatzambide-Geigel A. (1996). « La invencion del Caribe en el siglo XX. Las definiciones del Caribe como problema historico e metodologico », Revista Mexicana del Caribe, Ano. 1, Num1, p75-96.

Girvan N. (2005). « Reinterpreting the Caribbean », in Pantin D. (Ed.) The Caribbean economy, a reader, Kingston, Ian Randle Publishers.

Thomas-Hope E. (2002). Caribbean migration. Kingston, University of the West Indies Press.